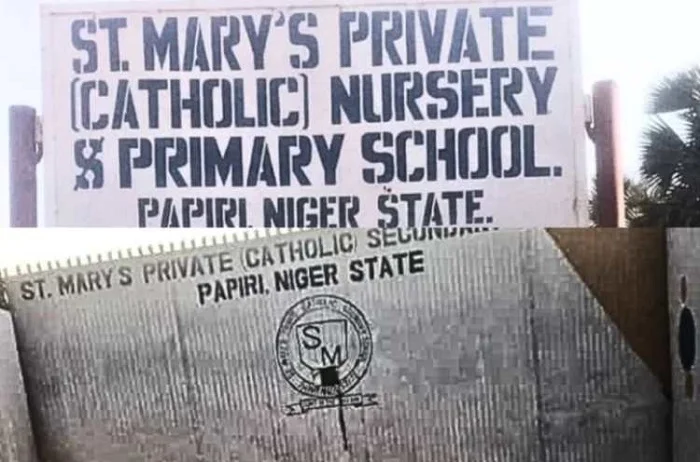

The escalating crisis of mass abduction in Nigeria has once again gripped the nation and captured global attention, following the brazen raid on St. Mary’s Catholic School in the remote Papiri community of Niger State. While a fragile sigh of relief swept across the nation with the news of 50 pupils escaping captivity, the joy is profoundly muted by the staggering reality that 265 students and teachers remain missing, held by armed bandits whose trade is tearing the fabric of Nigerian society apart.

The event, which occurred just days after a separate mass kidnapping in neighboring Kebbi State, initially saw conflicting figures. However, verified reports from school authorities and the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) established that the total number of individuals seized—including students and 12 teachers—stood at an alarming 315. The subsequent escape of 50 students, aged between 10 and 18, who slipped away individually between Friday and Saturday, highlights both the chaos of the bandits’ operations and the desperate courage of the children. Yet, it leaves a core group of 253 students and all 12 teachers unaccounted for, confirming the incident as one of the largest school abductions in the nation’s history, surpassing the infamous 2014 Chibok tragedy in initial scale.

This latest attack serves as a chilling testament to the utter failure of Nigeria’s security architecture to protect soft targets, especially educational institutions. The St. Mary’s school, a co-educational secondary school, was located in a region often plagued by criminal gangs who exploit the vast, ungoverned forests straddling several states. These perpetrators, known locally as bandits, are primarily motivated by the lucrative kidnapping-for-ransom economy, which has rapidly replaced cattle rustling as their main revenue stream. The strategic targeting of schools, particularly boarding facilities, ensures high-profile attention and massive ransom payments, directly funding their further armament and expansion.

The government’s response has been marked by a mixture of decisive symbolic action and criticized operational silence. President Bola Tinubu, reacting to the wave of insecurity, cancelled scheduled international engagements, including participation in the G20 summit, underscoring the severity of the crisis. Simultaneously, the Niger State Governor, Mohammed Umar Bago, ordered the immediate and indefinite closure of all schools in the state as a precautionary measure, a move that neighboring states have also adopted. While intended to safeguard lives, this policy decision carries a devastating double-edged sword: it validates the bandits’ terror strategy by disrupting education and threatens to reverse decades of educational progress, particularly for the girl-child, who is disproportionately affected by the fear of abduction.

The emotional and psychological toll on the victims’ families and the immediate community of Papiri is unimaginable. Parents are subjected to an excruciating wait, punctuated only by agonising rumours and the government’s generalized assurances. The global outcry, led by figures like Pope Leo XIV, who expressed being “deeply saddened” and made a “heartfelt appeal for the immediate release of the hostages,” underscores the international urgency of the situation. Nigeria faces a defining moment: the state must pivot from reactive damage control to a proactive, comprehensive security strategy that includes fortifying schools, enhancing intelligence gathering, and decisively confronting the non-state actors that have rendered large swathes of the country ungovernable. The safe return of the remaining 265 victims is not merely a humanitarian objective; it is a critical necessity for restoring faith in the Nigerian state. Until then, the shadow of St. Mary’s abduction will continue to darken the national landscape.